Built for the systems your business depends on.

Who We are

Sparq is built by people who’ve carried real operational responsibility, combining deep engineering expertise with practical judgment to deliver results that hold up in production.

Who We are

Sparq is built by people who’ve carried real operational responsibility, combining deep engineering expertise with practical judgment to deliver results that hold up in production.

Our origin story

We integrate directly into complex environments and move work forward with clarity, accountability, and operational focus.

We deliver momentum early and reinforce it with systems designed to perform as scale, load, and change increase.

We remove friction—technical, organizational, and economic—so teams can modernize without unnecessary cost or disruption.

our core values

We build inside the work. Decisions, tradeoffs, and accountability stay close to execution.

Every initiative ties directly to measurable impact: margin, throughput, reliability, or time-to-impact.

Intelligence is embedded into workflows where decisions are made and outcomes are measured.

We engineer solutions that operate within the platforms and tools organizations already depend on.

Systems are engineered to be clear, usable, secure, and durable under real operating conditions.

We communicate directly and precisely so teams stay aligned and execution stays grounded.

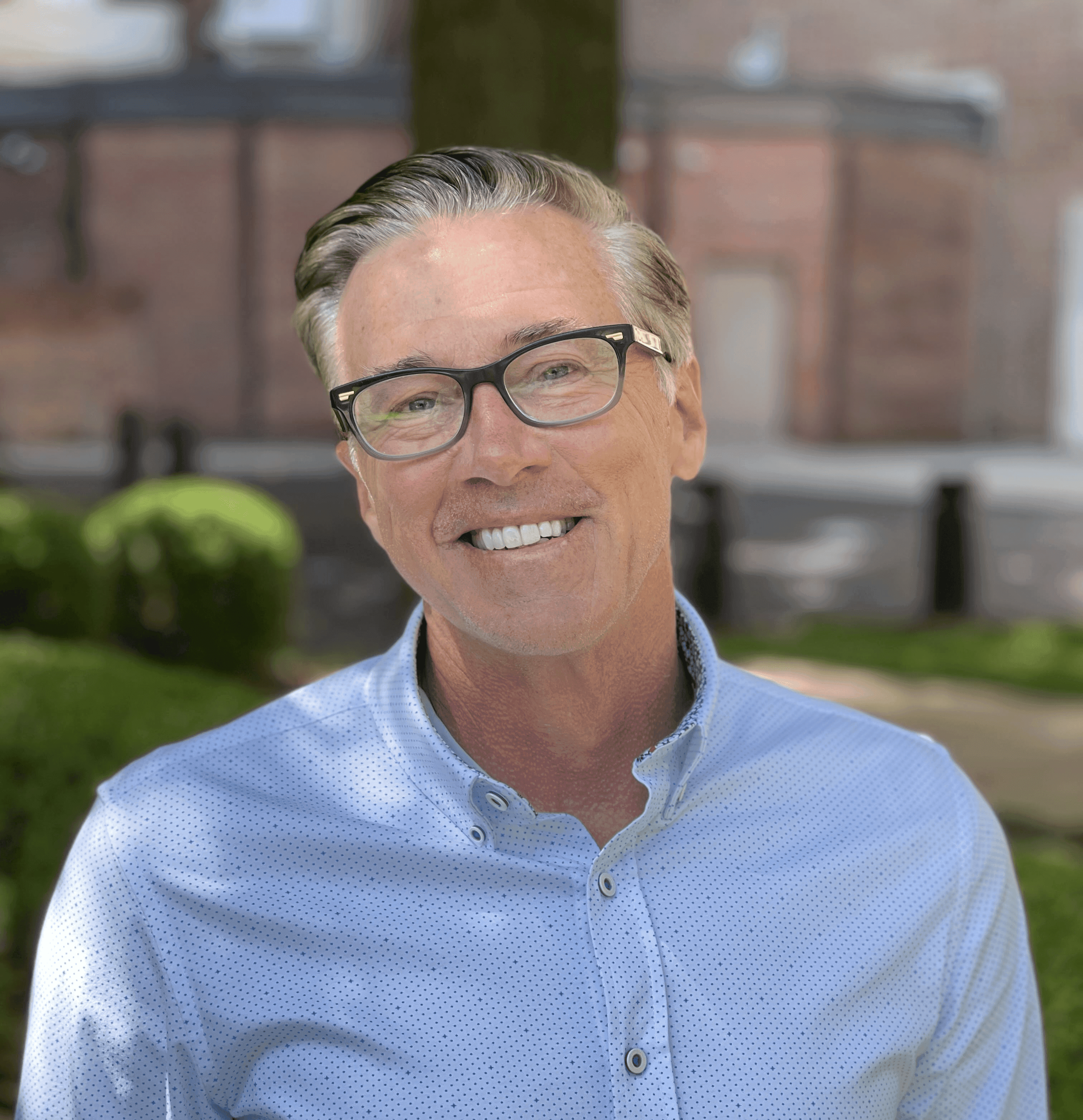

Meet Our Leaders

CEO

CEO and Executive Chairman of the Board of Directors

CTO

CPO

CGO

COO

CFO

CCO

REAL RESULTS

products delivered

years operating inside complex, high-pressure environments

REAL RESULTS

products delivered

years operating inside complex, high-pressure environments